Briefing Document: Nicolas Lee Behrmann’s “Jewish Worship as Environment for Encounter”

Date: October 26, 2023 Source: Excerpts from “Jewish_Worship_as_Environment_for_Encoun.pdf” (Cincinnati, Ohio, May 24, 1971)

Overview:

This document briefs the main themes and important ideas presented in excerpts from Nicolas Lee Behrmann’s 1971 Rabbinic Thesis, “Jewish Worship as Environment for Encounter.” The thesis explores the potential of Jewish worship services to become environments that foster meaningful interpersonal “encounter,” addressing the perceived decline in synagogue attendance and a growing sense of individual isolation in a rapidly changing modern world. Behrmann argues for incorporating multi-media techniques and experiential elements into traditional liturgy to create more engaging and relevant worship experiences.

Main Themes and Important Ideas:

1. The Dilemma of Capturing Non-Verbal Experience:

- Behrmann acknowledges the inherent challenge of translating a potentially profound non-verbal experience like worship into a linear, verbal academic format.

- The report on the thesis highlights this tension: “The effort to capture what is essentially a non-verbal experience in a linear verbal form is liable to become a highly frustrating task. It has in it a built-in failure. To the extent that the writer succeeds in conveying to the reader the power and appeal of the non-verbal aspects of worship, he undercuts his own premise.”

- This dilemma underscores the thesis’s central argument that the experience of worship, particularly its non-verbal and environmental aspects, is crucial and cannot be fully conveyed through text alone.

2. Jewish Worship as an “Environment for Encounter”:

- The core concept of the thesis is to view the Jewish worship service as a designed “environment” intended to facilitate “encounter.”

- Behrmann defines “environment” broadly to include “all forms of communication, both natural and man-made,” emphasizing that we constantly receive messages from our surroundings.

- “Encounter” specifically refers to “the verbal and non-verbal forms of communication which we send and receive from other people in our environment.”

- The thesis posits that by intentionally shaping the worship environment, it can become a space where deeper and more authentic interpersonal communication (“encounter”) can occur.

3. The Need for New Forms of Worship in a Changing World:

- Behrmann’s work is motivated by a perceived need for contemporary Jewish worship to adapt to the realities of modern life. He cites Rabbi Maurice N. Eisendrath’s concern about low synagogue attendance (less than 4%) and the need for “unlimited experimentation” in liturgy beyond superficial changes.

- Rabbi Eisendrath is quoted advocating for “widespread research, the coopting of the finest minds and souls in the realm of poetry, drama, art, are requisite for that revision of liturgy which will win from our contemporaries a more satisfying response.”

- The thesis recognizes the rapid pace of technological and social change, echoing Alvin Toffler’s concept of “Future Shock” and the resulting feelings of isolation and alienation described by Carl Rogers: “For the first time, he is freed to become aware of his isolation, aware of his alienation, aware of the fact that he is, during most of his life, a role interacting with other roles so he is seeking, with great determination and inventiveness, ways of modifying this existential loneliness.”

4. Addressing “Philosophical Neurosis” and the Desire for Meaning:

- Behrmann connects the need for encounter in worship to William Schofield’s concept of “philosophical neurosis,” where individuals, despite a lack of traditional complaints, experience a “painful awareness of absence—the absence of faith, of commitment, of meaning.”

- He draws on Erich Fromm’s distinction between “freedom from” and “freedom to,” suggesting that modern individuals have gained freedom from external constraints but often lack the inner direction and “positive freedom” to act authentically.

5. The Role of Responsibility and Spontaneity:

- The thesis highlights the emphasis in contemporary therapies (Reality Therapy, Gestalt Therapy) on individuals taking responsibility for their own behavior and becoming more self-aware. Fritz Perls is quoted: “Full identification with yourself can take place if you are willing to take full responsibility–response-ability–for yourself, for your actions, feelings, thoughts.”

- This emphasis on responsibility connects to the concept of “encounter,” which involves “a spontaneous self-responsible mode” of interaction.

- Behrmann also references Abraham Joshua Heschel’s discussion of keva (fixed ritual) and kavanah (spontaneous response) in Jewish prayer, noting the “perpetual danger of prayer becoming a mere habit, a mechanical performance.”

6. Utilizing “Festivity” and “Fantasy” in Worship:

- Drawing on the work of Protestant theologian Harvey Cox, Behrmann suggests incorporating elements of “festivity” (reliving the past) and “fantasy” (extending the frontiers of the future) into worship.

- Cox is quoted explaining the value of these concepts: “Festivity is a human form of play through which man appropriates an extended area of life, including the past, into his own experience … If festivity enables man to enlarge his experience by reliving events of the past, fantasy is a form of play that extends the frontiers of the future.”

- These elements are seen as ways to create an environment for encounter by providing present-tense engagement with tradition and stimulating imagination.

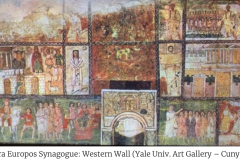

7. “Because It’s the Sabbath”: A Case Study in Multi-Media Worship:

- The thesis includes a detailed script for a Sabbath service titled “Because It’s the Sabbath,” which serves as a practical application of Behrmann’s theoretical framework.

- The service utilizes a multi-media approach, incorporating slides, recorded audio (including popular music like The Beatles), incense, and dramatic elements.

- Key themes of the Sabbath explored in the service include the Sabbath as the seventh day of creation (emphasizing menucha – rest, happiness, stillness, peace) and the Sabbath as a bride (drawing on the joyous imagery of a wedding celebration). Heschel’s concept of the Sabbath as “a sanctuary in time” is central.

- The service structure interweaves these themes through music, visuals, readings (including traditional texts like “Lecha Dodi” and the creation narrative), and enacted rituals like a dramatized “wedding” of the Sabbath bride and Israel.

- A significant element is the intentional creation of “encounter” opportunities, such as dividing the congregation into small groups for a silent devotion and a shared experience of acknowledging the “good” in each other through eye contact.

8. Guidelines for Constructing a Worship Environment:

- The thesis concludes with a set of guidelines for others interested in creating similar experiential worship services. These guidelines emphasize:

- Identifying the main themes and associated emotions.

- Analyzing the existing environment and its congruence with the desired mood.

- Utilizing liturgy (words, music, visuals, rituals) to effectively convey themes and create moods.

- Ensuring the service allows for experiential engagement rather than passive reception.

- Inviting active participation from the worshippers.

- Drawing upon and respecting tradition.

- Creating a cohesive and organic whole with the various elements.

- Embracing brainstorming and experimentation.

- Evaluating the service and incorporating feedback.

Quotes Highlighting Key Ideas:

- On the challenge of verbalizing non-verbal experience: “The effort to capture what is essentially a non-verbal experience in a linear verbal form is liable to become a highly frustrating task. It has in it a built-in failure.”

- Rabbi Eisendrath on the need for liturgical innovation: “…widespread research, the coopting of the finest minds and souls in the realm of poetry, drama, art, are requisite for that revision of liturgy which will win from our contemporaries a more satisfying response.”

- Carl Rogers on modern alienation: “For the first time, he is freed to become aware of his isolation, aware of his alienation, aware of the fact that he is, during most of his life, a role interacting with other roles so he is seeking, with great determination and inventiveness, ways of modifying this existential loneliness.”

- William Schofield on “philosophical neurosis”: “The absence of conflicts, frustrations, and symptoms brings a painful awareness of absence—the absence of faith, of commitment, of meaning…”

- Abraham Joshua Heschel on the nature of the Sabbath: “The sabbath itself is a sanctuary which we build out of time, a sanctuary in time.” and “the primary awareness is one of our being within the Sabbath rather than of the Sabbath being within us.”

- Heschel on keva and kavanah: “…there is a perpetual danger of prayer becoming a mere habit, a mechanical performance, an exercise in repetitiousness….”

- Fritz Perls on responsibility: “Full identification with yourself can take place if you are willing to take full responsibility–response-ability–for yourself, for your actions, feelings, thoughts…”

- Harvey Cox on festivity and fantasy: “Festivity is a human form of play through which man appropriates an extended area of life, including the past, into his own experience…” and “fantasy is a form of play that extends the frontiers of the future.”

Conclusion:

Behrmann’s thesis presents a compelling argument for re-envisioning Jewish worship as a dynamic and engaging “environment for encounter.” By drawing on contemporary understandings of communication, psychology, and the changing needs of individuals in modern society, he proposes a shift towards more experiential and multi-sensory forms of worship. The detailed script for “Because It’s the Sabbath” provides a concrete example of how these principles can be applied, while the included guidelines offer a framework for future innovation in Jewish liturgical practice. The work underscores the importance of addressing the spiritual and social needs of contemporary Jews by creating worship experiences that are both rooted in tradition and relevant to the present.convert_to_textConvert to source